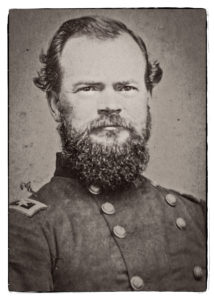

He was born in Ohio in a small town in Sandusky County before it was a town. Today, the citizens of Clyde proudly honor his contribution to the Nation by giving him his rightful place in their community. He would grow up to play a pivotal role as a U.S. General commanding the right wing of General Sherman during his campaign to take Atlanta during the Civil War.

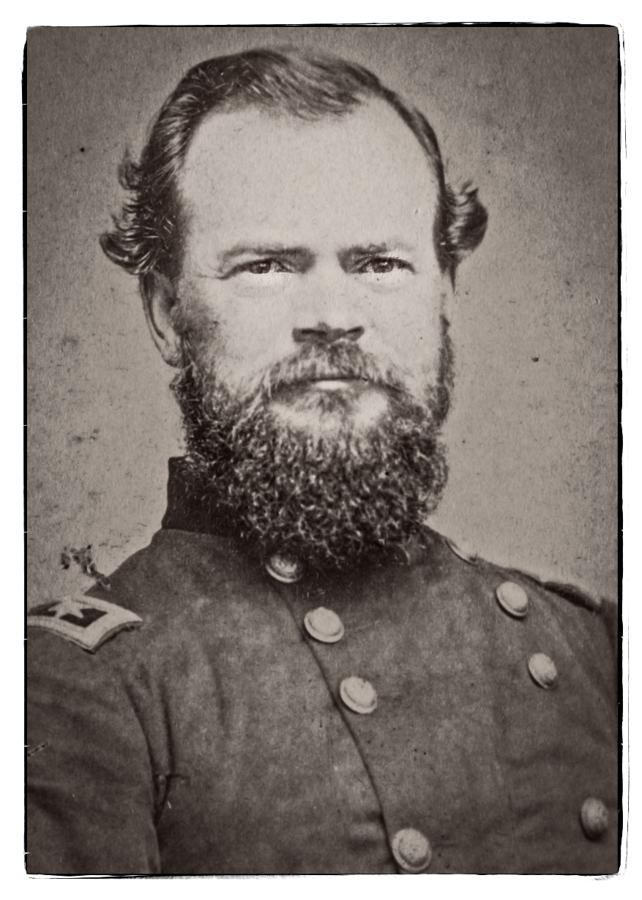

McPherson had been with Sherman for a long time including the siege of Vicksburg the following year. As Sherman would later say, his good friend and right hand, was James McPherson. When James asked Sherman for a short leave so he could marry his fiance in Baltimore, Sherman denied that request. A decision he would openly regret a few months later.

After his death, his body was returned to Clyde and buried in the family cemetery not far from the home where he was born on November 14, 1828.

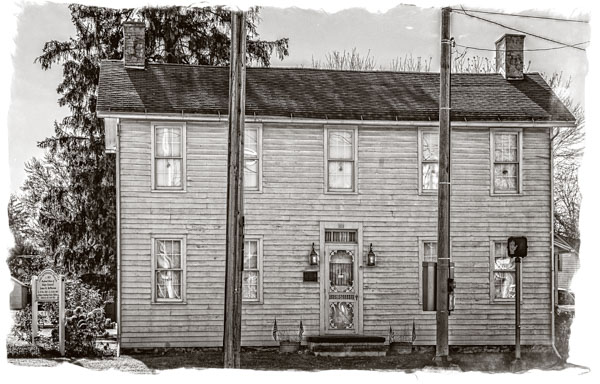

James Birdseye McPherson was the first born son of William and Cynthia. William had come to this area from New York state 5 years before to purchase some land, build a house for his bride-to-be. He came with several of his friends, one of them was James Birdseye for whom William would name his son.

William was a blacksmith and a farmer. From some records it indicates that he may have had a quick to rise temper. Like many of his friends that would later join him in Sandusky County, his family were Scottish. He purchased a rather substantial piece of land that was at the time known as Hamer’s Corners (this name would later be changed to Clyde in honor of Clyde New York which was named for the Clyde River in Scotland).

Four years after the McPherson’s set up household in Hamer’s Corner, Cynthia gave birth to James B. McPherson. No description of this birth or of the baby was recorded, but many years later after James’ death, his mother Cynthia related a story that when he was 3 weeks old a group of Seneca Indians stopped in at their house to see the new baby. One of them declared: “He will be a great man.”

When James was 11, the country experienced a major financial crisis that became known as the Panic of 1837 which was similar in scope to the 2008 financial crisis experience that lasted seven years. Banks failed, businesses failed, prices declined and thousands of workers lost their jobs. Unemployment rose as high as 25% in some areas.

Like most businessmen of the day, the Panic of 1837 caused dramatic changes in William first in his financial health and then later his physical health. The stress of his losses and his efforts to try and protect his family ultimately caused him to become bedridden. Since the family business had collapsed, young James found it necessary to work for others in order to help provide for the family. At the age of 12 he had become the man of the family which would prove to have a long lasting effect on him and his career.

Fortunately, James was able to find work as a clerk in Sterntown (known today as Green Springs located about 6 miles southwest of Hamer’s Corner). Robert Smith the owner of a general store and the local mill adopted James (not legally). They exposed him to a rich education where he learned to read, appreciate music and was exposed to a variety of people one of those being Rutherford B. Hayes who was six years older than James and the two became good friends. It was through the Smith family and Rutherford that several years later afforded him the opportunity to move up in the world when he became a West Point cadet.

In 1847 James’ father died. The following year 19 year old James left home for West Point. He would never return to Hamer’s Corner other than for short stays.

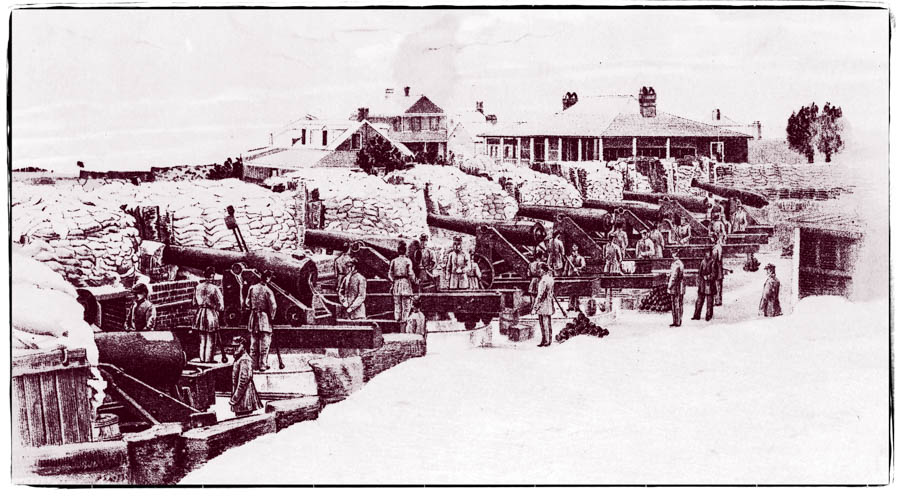

During the battle for Atlanta, General McPherson was at General Sherman’s tent discussing what McPherson thought about how the Confederate would attack. It was in Sherman’s mind that the Confederates were retreating from Atlanta, but McPherson was certain they were setting up an attack of the Union’s flank and rear. It was a heated discussion and ongoing when a large volume of gunfire erupted in the direction of where McPherson’s troops were located and confirming his belief that Confederate forces were mounting an attack and that attack had begun.

McPherson quickly returned to his men until he reached his XVI Corps. Here he found his men struggling against an overwhelming advance of Confederate forces. Realizing the importance of this contact, McPherson decided to personally go on to his XVII Corps so they could be brought to bear upon the advancing Confederates.

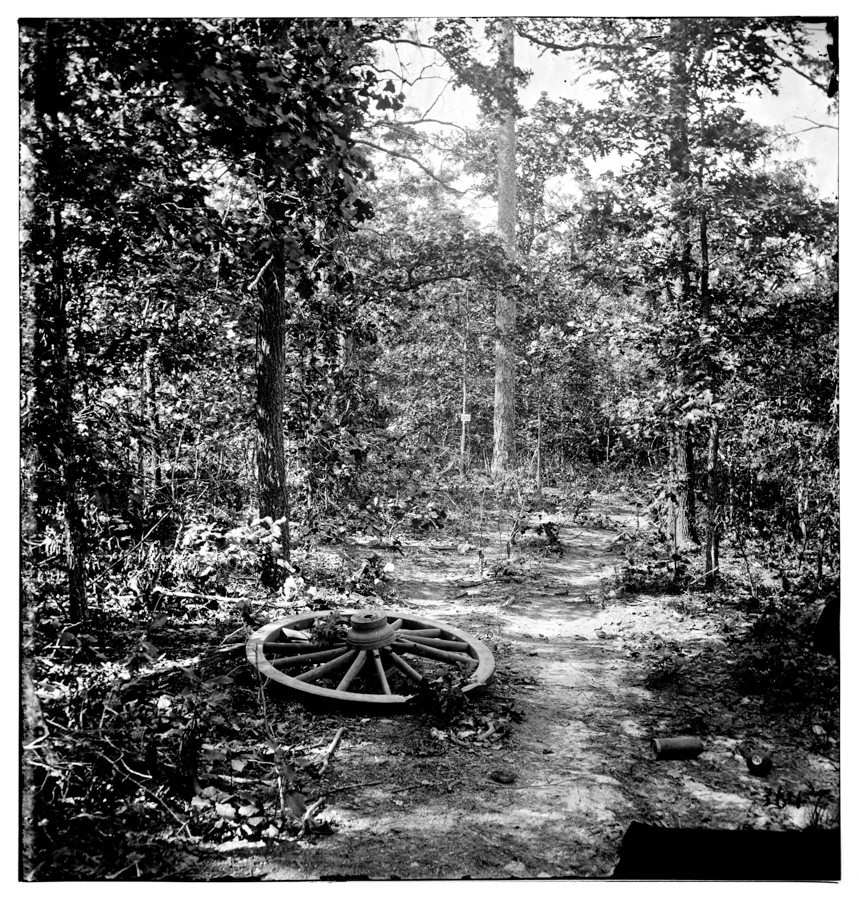

McPherson’s two corps were separated by a thick woods which he had to navigate to reach his XVII Corps. McPherson, his aide and Colonel R.K. Scott were alone when they came upon a Confederate skirmish line. Both sides were suddenly taken back, and the Confederate skirmish line of 3 or 4 men simultaneously yelled for the two Union men to halt. Realizing what was about to happen if he were to be captured, McPherson and his aide wheeled their horse and bolted. The skirmish line reacted with volley of fire. McPherson’s aide turned in his saddle and saw the line taking aim and he later reported sliding around in his saddle so his horse was between him and the enemy. Unfortunately, James Birdseye McPherson was hit and killed, becoming the highest ranking Union officer to die in battle.