September 1: What began in early May was reached its ultimate goal: the surrender of Atlanta in 1864. On this day Ohio born William Tecumseh Sherman, supreme commander of the armies in the west, forced Confederate defenders of this key military supply center, to give way. After 4 months of bitter fighting, Confederate General John B. Hood decided he could no longer defend the city from Sherman’s encircling Union forces. At 2:00 A.M. fires were set to munition train cars that resulted in terrific explosions that Sherman could hear 20 miles away and recorded in his field notes. Sensing that Hood had retreated, Sherman ordered reconnaissance parties to survey the city. It was one of these reconnaissance parties under command of General Henry W. Slocum that encountered Mayor James M. Calhoun and several other Atlanta citizens under a flag of truce, officially surrendered the city on the morning of September 2, 1864.

When Sherman received word from Slocum that Atlanta was theirs, Sherman telegraphed Lincoln on September 3 that read: “Atlanta is ours, and fairly won”. After this Sherman ordered all civilians to leave the city

After it was clear to Sherman that the city was safe to enter, he set up his headquarters in town. On September 8 Sherman’s orders to evacuate all citizens from the city went into force. In compliance with this order, Mayor Calhoun notified Atlanta’s citizens they had to first register with the Union commander the number of household members departing and the number of packages being carried. Once they registered, they were given safe travel permits. Those registration records show that 705 adults, 860 children and 86 servants along with 8,842 packages left Atlanta by the end of September.

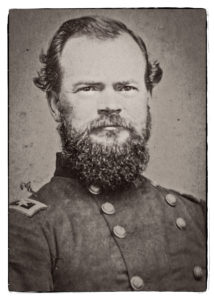

For Sherman taking Atlanta had been a necessary task, but also a costly achievement. His men suffered 3,641 casualties, among them his good friend and another man from Ohio, Major General James Birdseye McPherson, the highest ranking Union officer to die in battle.

When Sherman left Atlanta in November, instead of pursuing Hood, he set his sights on Savannah and began what became known as “Sherman’s March to the Sea” leaving a wide path of destruction that would help bring an end to the long war the following spring.

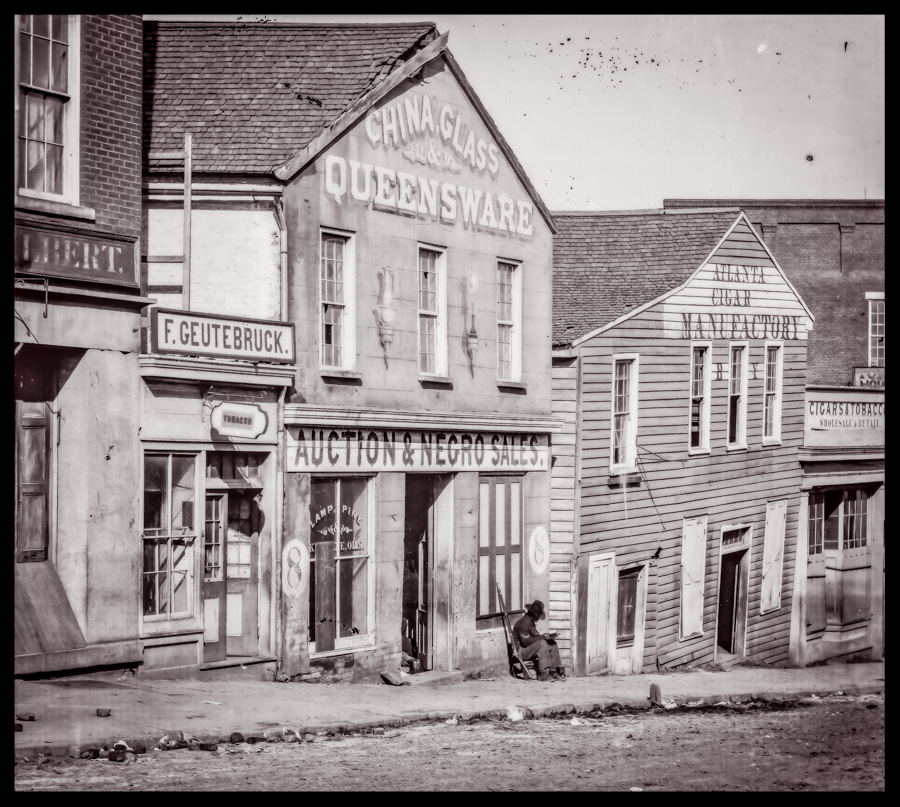

Before departing for Savannah, Sherman and his men remained in Atlanta for 2 ½ months during which his war weary troops gathered supplies, recuperate, and destroyed the rail lines. It was during this time frame that George N. Barnard, an official photographer of the Chief Engineer’s Office, documented Atlanta. However, most of the areas he photographed would be destroyed in November when Sherman’s men began destroying the remaining munition depots creating a firestorm that destroyed most of Atlanta.