In 1865 this was Good Friday. It had been five days since General Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia, but the War o f Rebellion was still not over. Confederate General Johnson still had 90,000 men under his command. Some thought he could be massing an assault on Grant in Virginia. Even with that lingering threat, the last 5 days were days of celebration in the District. The President had just returned from Richmond where he went to see the total destruction of the Confederate Capital. Near exhaustion he didn’t feel like going to the theatre, but he promised his wife Mary. Plus, his attendance had already been announced for Friday night’s performance.

Mary requested General Grant and his wife to accompany her and the President, but the general had plans to be in Philadelphia so she requested their friends Major Henry Rathbone and his fiance Clara Harris to accompany them. They accepted and the two couples arrived promptly at 8:30 at the theatre.

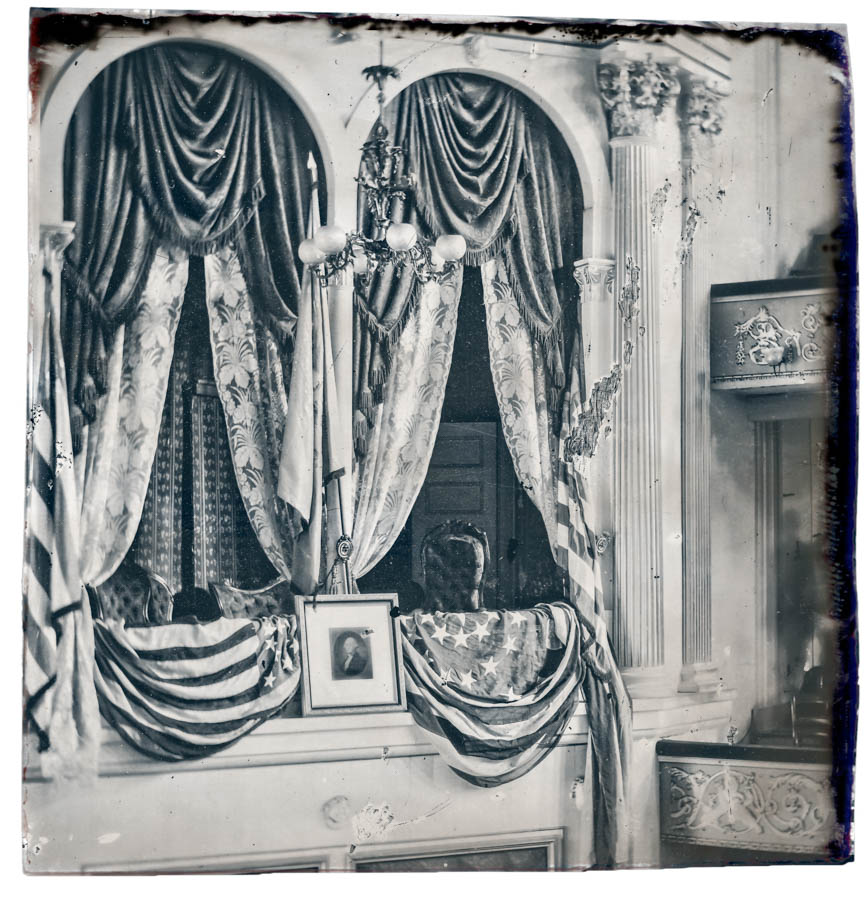

Ford’s Theatre Presidential Box is located on the 2nd tier and was entered from the Dress Circle through a narrow corridor about 3 feet wide and 10 feet long. The box looked directly down on the right side of the stage. Inside the box were two small chairs, a settee and an upholstered rocker the president used. All of these seats were angled toward the stage except for the settee, which is where Clara Harris sat. The president’s rocker was nearest to the door and the others in the room would have been further forward of his position.

The door to the Presidential Box was unlocked and unguarded when the president arrived. Earlier in the day, one of the actors had cut a small peep hole in one of the doors so he could see the President without being noticed.

At about 10:15 P.M., halfway through Act III, Scene 2, the character of Asa Trenchard, played that night by Harry Hawk, utters his line, considered one of the play’s funniest that always brought hilarious laughter from the audience. It was at this point that the actor standing behind Lincoln knew would be his cue. He quickly fired his .44 caliber derringer. Some in the audience may have heard the shot, but most did not. Perhaps someone dropped something, nothing more. Even in Lincoln’s box, the sound wasn’t immediately identified as coming from their location.

The President’s head slumped slightly forward as if he had nodded off. Thinking the loud sound was part of the on stage clamor, Mary reached over and touched her husband, perhaps so he wouldn’t miss the events on stage. Everyone was laughing. She pulled her hand back and even in the dim light she noticed blood on her fingers. That’s when her screaming began. Everything seemed to happen at once. The actor pushed his way forward. Major Rathbone realized something had happened and reached out to grab the actor’s sleeve as he made his way to the balcony railing. The actor quickly swung a dagger at the major slashing the his arm, then leapt over the railing, landing awkwardly. Now everyone in the large theatre seemed aware something dreadful had happened. The actor shouted a few words that most could not understand then limped across the stage in front of a stunned audience to a side exit.

On the second tier Mary’s screaming intensified when she saw Clara Harris’ evening gown stain bright red, which Mary thought was from her husband’s wound, but was in fact from the major’s wound. The long gash on his arm was bleeding profusely and in just a few moments he had collapsed from loss of blood. The president’s wound, although fatal, there was little bleeding.

In the audience Charles Taft, a surgeon was lifted up to the Presidential Box where the president was lying. As the box quickly became swarmed with additional people, it was decided to take him down to someplace where they could find a more suitable place for the doctors to work their miracles.

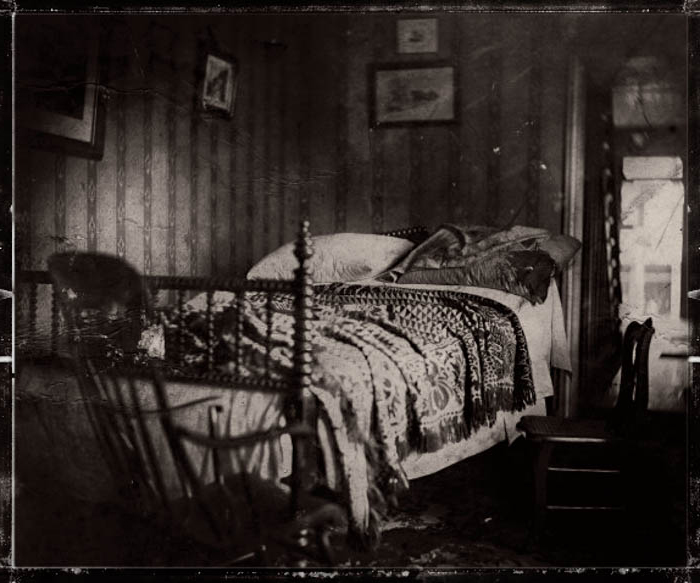

There would be no miracles tonight. After being carried across the street to a boarding house, the president died the following morning without ever regaining consciousness. The country which had seen hundreds of thousands of its men die in a war that lasted more than 4 years, was suddenly thrust into a national state of mourning.

Thirteen days later the President’s funeral train would be arriving in Cleveland and the following morning in Columbus on its way to Springfield, Illinois. Although embalming had begun to be used, it was not a perfected science. By the time the President’s casket arrived in Columbus, 100s of lilac blossoms were needed to mask the smell of death. The country was facing the awful cost of a tearing itself apart.