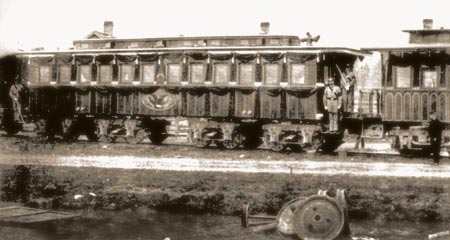

Lincoln’s Funeral Train of 9 cars pulled by the locomotive The Nashville left Cleveland at 10:30 p.m. for it’s overnight trip to Columbus. All along the way at every depot, large bonfires were lit to light the way for the Funeral Train. Thousands gathered in the torrential rains that fell all through the night, to catch sight of the passing funeral train. In the car called “America” all the way to the back was the black draped coffin of Lincoln. In the front of the same car was the smaller casket of Lincoln’s son Willie who died in 1862.

At 6:32 a.m. the funeral train passed through Lewis Center, then, just as the train was rolling through Worthington at 6:56 a.m., the rains began to let up and by 7:30 a.m. as the train pulled into Union Station, the gloomy overcast skies began to break. The military escort had already assembled and been waiting patiently since 6:00 a.m. to take the coffin to the Statehouse.

That morning in the Saturday edition of The Daily Ohio State Journal an itinerary was published so that mourners would know where Lincoln’s casket would be at what time. Residents were also asked to appropriately decorate their homes along the parade route.

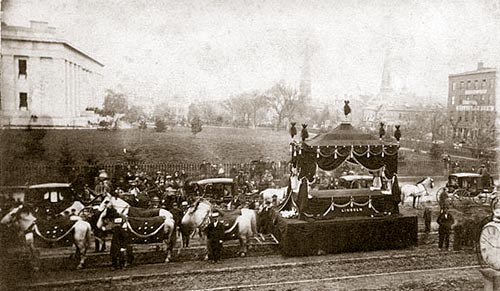

Long before the funeral train arrived at Union Station on the north side of the city, the order of the funeral procession had been determined. A special hearse had been constructed. The black broadcloth draped hearse was big: 17 feet long, 8-1/2 feet wide and more than 17 feet tall (today’s semi trucks are less than 14′ tall). The entire structure resembled a Chinese pagoda. Around the cornice of the canopy were 36 silver stars.

Once the train arrived at Union Station the casket was transfer by the 29 man military escort of veterans to a hearse pulled by 6 white horses, with black blankets across their back and black feathered plumes attached to their head. Besides the military escort, the hearse was also followed by the Mayors of both Columbus and Cincinnati as well as City Council members of both cities. Twenty-two honorary pall bearers including many of Columbus’ prominent citizens (Robert Neil, Fernando Kelton, Lincoln Goodale, and D. W. Deshler). Today, Kelton House is a museum of the Victorian era, and one of the artifacts on display is a lithograph of the funeral procession, along with the actual armband that Fernando wore performing his duties as a pall bearer.

The entourage traveled south on High Street to Broad, went east on Broad and then turned south on 4th Street. It then traversed through several downtown neighborhood streets until coming back on Town Street to High Street. From there it would go north to the west entrance of the Capitol Building.

All along the way 1000s of mourners lined the streets with the houses and businesses draped in black. Some youths with plenty of stamina, kept pace along side the hearse during the entire route.

At the West Gate of the Statehouse (today, this is where the McKinley Monument stands) an arch was built over the large gate posts. At the center of the arch were the words: “Ohio Mourns”. The Statehouse columns were wrapped in in black cloth to create spirals. Above the columns on the cornice a sign hung with a quote from Lincoln’s last inaugural address:

“With malice to none. With charity for all.”

Each of the Statehouse windows were heavily draped in black. Directly above the west door was placed the inscription

“God Moves in a Mysterious Way.”

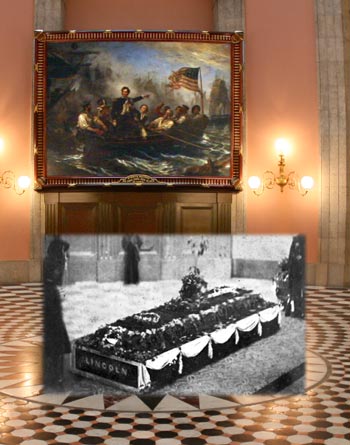

Just before 9:00 a.m. the process came to a halt on South High Street near the west gate to Capitol Square. There is a break in the gray clouds and sunlight spreads across those gathered. At about 9:00 a.m., the head of the procession arrived at the west entrance to Capitol Square. The 88th Ohio Volunteer Infantry was acting as special escort. They formed 2 lines on either side of the walk from the west gate to the entrance. Eight Sergeants of the honor guard placed the casket on their shoulders and slowly walked up the walkway and into the Rotunda. All around the Rotunda were fresh floral arrangements.

The bier, where the casket would be placed, was covered with lilacs that had just come into bloom throughout the city. When the casket was lowered to the flowery bier which sat upon a carpet that helped cut down on the echo of footsteps across the marbled floor, the 6’6″ long casket with Lincoln’s body, crushed the lilacs in such a way that the room was filled with smell of the fragrant lilacs. Although Lincoln’s body had been embalmed before leaving Washington D.C., the process was not yet perfected and his body had already begun to deteriorate badly giving off a putrid odor that had to be masked by the floral arrangements. To help preserve the President’s body during the 12 day trip back to Springfield Illinois, it would be packed in ice. A mortician also accompanied the body and applied chalk to Lincoln’s face to mask the discoloration.

Two sets of lines formed on High Street, one stretching north to Long Street and another south to Rich Street. It was estimated that 8,000 people an hour walked past the casket.

At 3:00 p.m. on the east side of the Capitol Building, a platform had been erected where state and local dignitaries and military generals spoke about Lincoln’s contributions. The feature speaker was General Hooker.

At 6:00 p.m. the doors to the Capitol were closed, a bugle sounded the assembly and the soldiers reformed for the final escort back to Union Station following the same route in reverse. From Columbus the funeral train would move on to Indianapolis, then to Chicago, and finally down to Springfield, Illinois for final burial.

After the casket was removed from the Rotunda, the doors to the Statehouse were re-opened and visitors continued to quietly pass through the great room where Lincoln’s body had laid in repose. After the last visitor passed through, the flowers from the bier and the floral displays around the room were collected. These flowers were then auctioned off and the money collected was donated to charity groups throughout the city that were helping wounded veterans returning from the Civil War.

The original plans for the funeral train called for it to travel on to Cincinnati for another public viewing. However, due to the condition of Lincoln’s deteriorating body, it was decided to forgo the Cincinnati stop, and move on to Indianapolis, then Chicago and finally to Springfield, Illinois.